Chandrayaan-1, India’s first Moon mission

Highlights

Chandrayaan-1 was India’s first mission to another world.

The orbiter discovered water on the Moon, catalyzing plans by nations to further explore our cosmic neighbor and even send astronauts.

Technologies developed for Chandrayaan-1 kickstarted a promising Indian planetary science program with increasingly ambitious missions.

On October 22, 2008, an Indian PSLV rocket launched the Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft into Earth orbit. After a series of orbit-raising maneuvers, Chandrayaan-1 successfully entered orbit around the Moon on November 8 of that year.

Over the next four days, it fired its engines multiple times at precise intervals to attain a circular orbit of 100 kilometers (62 miles) so it can closely study the Moon with its 11 instruments, roughly half of which came from NASA and space agencies in Europe. Communication with the orbiter was lost on August 29, 2009 but the mission’s key objectives were met, including discovering water on the Moon.

Why did India launch Chandrayaan-1?

The Mission Director of Chandrayaan-1, Srinivasa Hegde, recalls the mission’s inception in an interview as being thanks to Dr. K. Kasturirangan. During his time as chair of the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) from 1994 to 2003, Kasturirangan wanted ISRO to play a small role in India’s ambition to become a superpower. This planted the seed for undertaking more ambitious missions. The idea of a Moon orbiter was floated around and was received positively by everyone.

At the time, ISRO already had satellites designed for geostationary orbits, which could carry plenty of fuel on board. The basic infrastructure was ready and the only change required was adapting a geostationary satellite for the Moon. Initial calculations showed that India’s PSLV rocket could provide an Earth-bound orbit beyond which the fuel on the spacecraft could be used to go to the Moon and perform orbital capture. In all, Chandrayaan-1 was a logical extension of ISRO’s capabilities.

How did Chandrayaan-1 discover water on the Moon?

Finding water on the Moon was a primary scientific objective when ISRO was planning Chandrayaan-1. Space agencies globally were keen to confirm water’s presence, hopefully in relatively large amounts, as that would have implications for future human settlements as well as the Moon’s origin. NASA pitched and got to fly two of its water-hunting instruments on Chandrayaan-1.

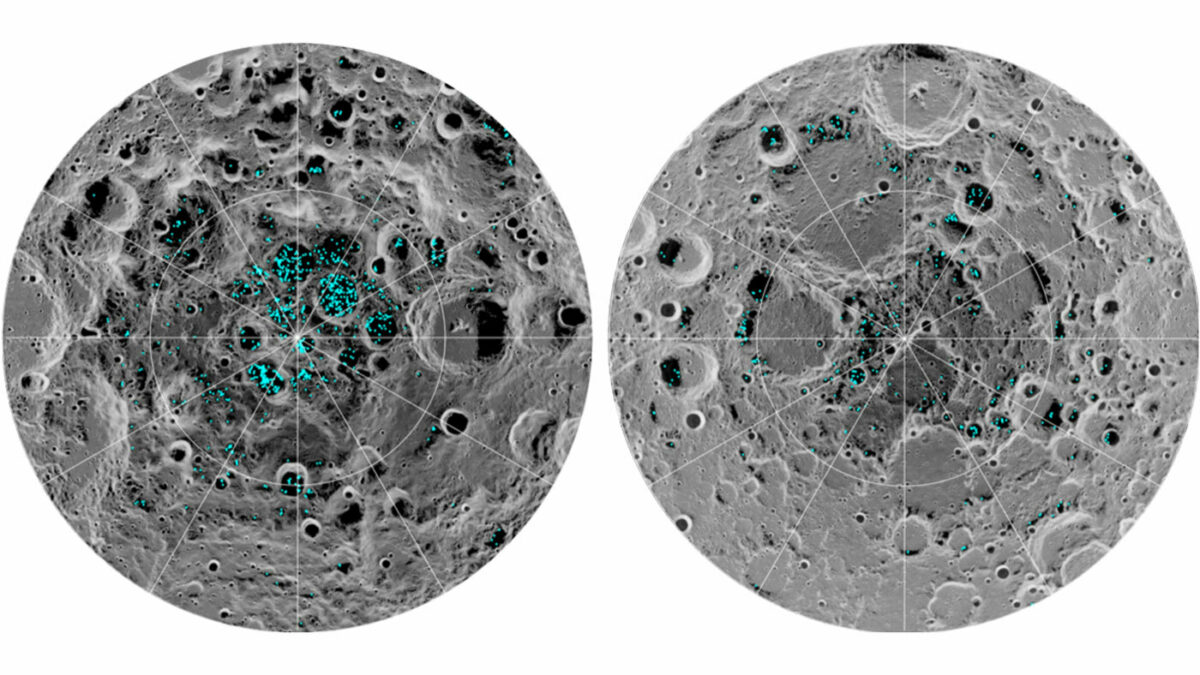

Their Miniature Synthetic Aperture Radar (Mini-SAR) found the patterns of reflected signals from more than 40 polar craters to be consistent with water ice. But just like with previous efforts such as NASA’s Clementine Moon-mapping orbiter, the mini-SAR data on its own wasn’t bulletproof. But Chandrayaan-1 carried with it another instrument, NASA’s Moon Mineralogical Mapper (M3), that could differentiate between ice, liquid water, and water vapor based on how the lunar surface reflected and absorbed infrared light. It was M3 that confirmed our Moon hosts water once and for all, and found the majority of it to be concentrated on the poles.

Among the many more scientific results from other Chandrayaan-1 instruments, the Indian and European Space Agency’s (ESA) collaborative instrument SARA stands out. By analyzing how protons (hydrogen nuclei) in the solar wind impact the Moon and get reflected, SARA helped scientists better estimate the amount and distribution of water or hydroxyl locked in the soil across the Moon. The discovery proved timely for ESA’s BepiColombo mission to study Mercury, which carries two similar instruments for detecting water.

What was Chandrayaan-1’s impact on lunar exploration?

Chandrayaan-1’s discovery of lunar water helped revitalize global interest in exploring our Moon. This includes NASA’s Artemis plans to return humans to the Moon and use resources like water to sustain future habitats as well as the flurry of upcoming robotic missions seeking the exact nature, state, and amount of lunar water.

There’s also India’s own Chandrayaan-2 orbiter, which uses its advanced radar to better map and quantify water ice on the Moon’s poles. South Korea’s first lunar orbiter KPLO will also help detect vast polar water ice deposits using its ultrasensitive camera. And NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer orbiter will map the form, abundance, and changes in water in sunlit regions on the Moon.

Surface missions like NASA’s upcoming VIPER rover will take a much closer look by physically studying water ice inside polar permanently shadowed regions, informing us how to extract the water to live on the Moon sustainably. VIPER’s findings will set the stage for NASA’s Artemis campaign, which envisions an eventual long-term human presence on our Moon.

Cost and collaboration

Less-noticed aspects of the Chandrayaan-1 mission are its total cost of less than $100 million and its collaboration model. As evidenced by the mission’s discoveries, welcoming foreign instruments proved effective in increasing mission science without increasing costs.

For the participating agencies, they got to fly their instruments without having to build and launch an entire mission of their own. At the same time, experience gained from collaborating with NASA and ESA in developing planetary instruments helped ISRO make fully indigenous, state-of-the-art instruments for the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter. South Korea is now following this very model for its first lunar orbiter KPLO.

What technologies did ISRO develop for Chandrayaan?

Chandrayaan-1 was the first time India explored another world. To materialize the mission, ISRO developed a number of new technologies. They established the Indian Deep Space Network to communicate with the spacecraft and made the Indian Space Science Data Center to process and archive scientific data from the mission. Future missions like India’s popular Mangalyaan Mars orbiter would go on to leverage this infrastructure. Even Chandrayaan-1’s spacecraft structure design formed the basis for Mangalyaan. Later this decade, ISRO also intends to launch a Venus orbiter.

In the decade since Chandrayaan-1 flew in lunar orbit, India attempted a Moon landing with Chandrayaan-2 but the spacecraft unfortunately crashed at the last moment. ISRO will retry landing with Chandrayaan-3 next year. The Japanese and Indian space agencies will be launching a joint mission in 2024 or later called Lunar Polar Exploration (LUPEX) to explore water and other resources on the Moon’s south pole using a rover.

In all, Chandrayaan-1 launched not just a science orbiter to the Moon but India’s planetary program.

Acknowledgments: This page was authored by Jatan Mehta in 2022.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth